Inhalte

Toe Prosthesis from TT95

This artificial toe is most likely one of the oldest prosthetic devices in human history. It was discovered attached to the right foot of a female mummy buried in the cemetery of Sheikh ‘Abd el-Qurna at Western Thebes (Luxor) and examined in 1997 on behalf of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo (DAI). In 2001, the prosthesis was transferred to the Cairo Egyptian Museum and underwent conservation treatment. In 2016–2017, the Basel Life Histories of Theban Tombs (LHTT) Project reevaluated this one-of-a-kind object at the museum in cooperation with the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine at the University of Zurich (Switzerland) and an international team of experts.

Material Analysis

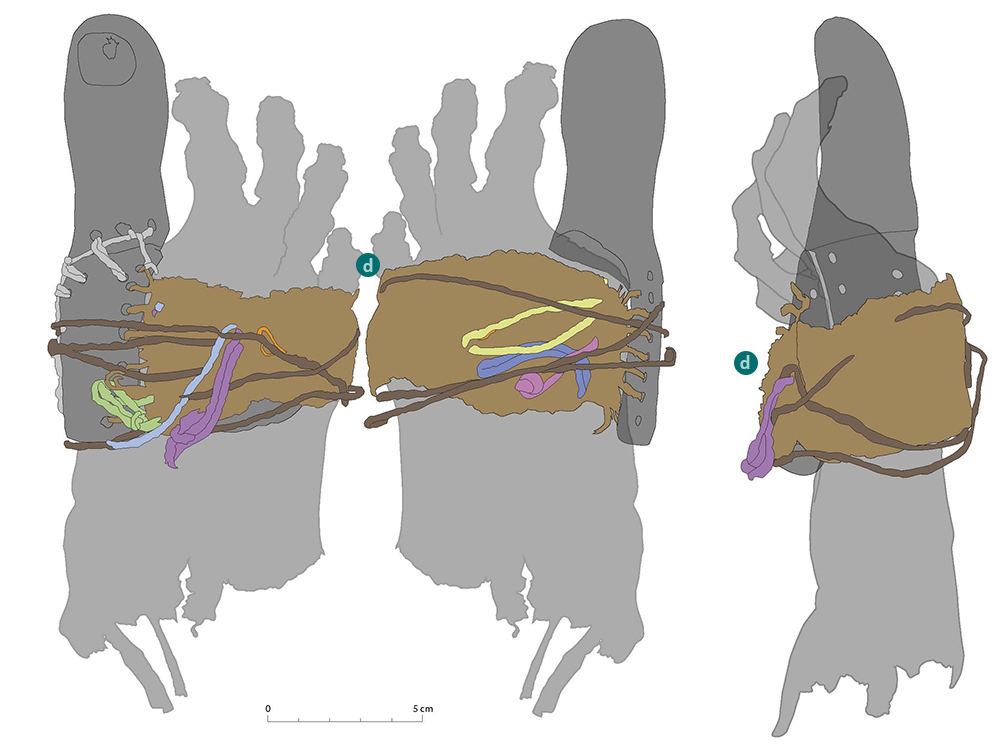

The investigations of the wooden big toe, conducted by the LHTT project, comprised modern microscopy as well as X-ray and CT technologies. The prosthesis consists of four individually crafted parts: the prosthetic device itself, composed of the big toe (a), a dorsal platelet (b), and a triangular side flap (c), as well as a textile belt strap (d). Parts (a)-(c) were tied together with cabled strings (e). Today, only the string that fastens the dorsal platelet (b) to the corpus (a) is preserved; like the belt strap, it was made of bast fibers, probably from flax. The strap was manufactured in the so-called twining technique, used in the production of basketry and textiles in Egypt and all over the world. This technique guaranteed both robustness and flexibility of the prosthetic band. Besides narrowing down the identity of the wood to an imported species from Africa (parts (a) and (b)), we were able to determine further materials used in the production of the prosthesis: raw hide (side flap (c)) and horn (inlaid toe nail). Sample analyses of these materials for precise identification, however, could not be conducted.

The Foot

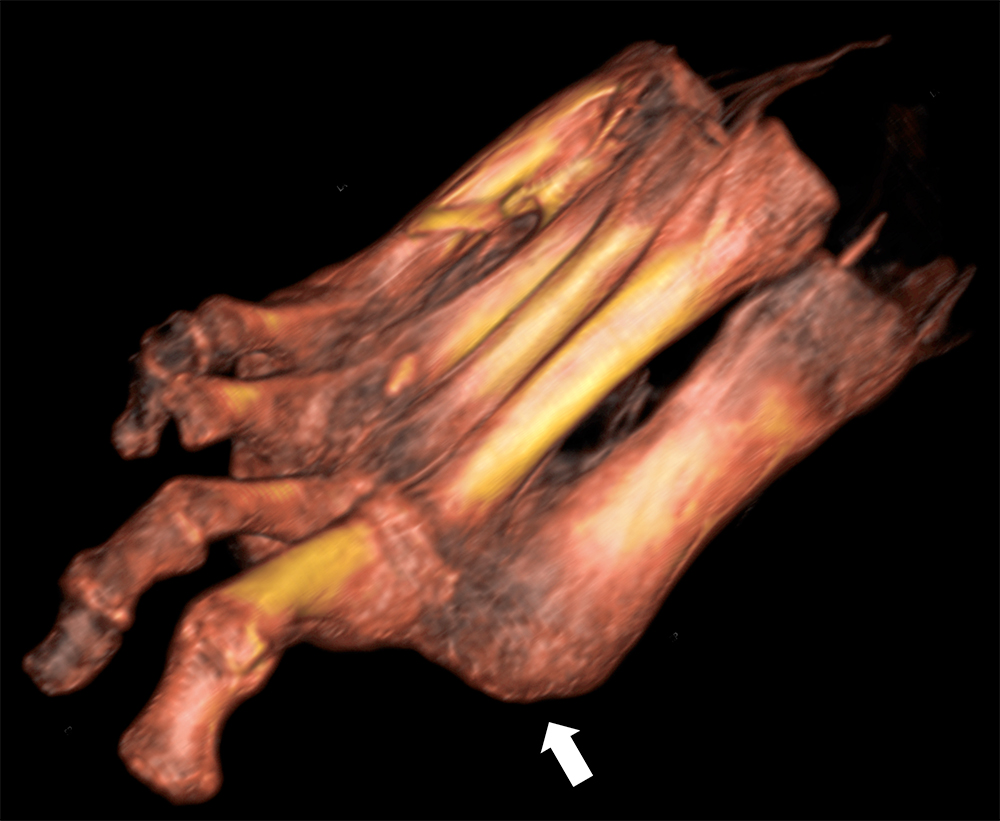

The 3D X-ray imaging of the foot shows the amputation of the big toe at the midfoot-toe joint. At this location, a very thin layer of soft tissue covers the underlying bone. The tissue may indicate that the loss of the toe took place during life time.

The Prosthesis’ Biography

The superbly carved and composed wooden big toe bears the hallmarks of an experienced and skilled master craftsman. He had given much attention to an aesthetic, natural appearance of the artificial limb, but also to the comfort and mobility of its female owner. The device was therefore readjusted to her foot several times. Besides traces of wear and repair, features of recarving could also be identified. This evidence suggests that the wooden toe was utilized by its owner over a longer period of time. After her death, the prosthesis was permanently fixed to the foot of her mummy. The various components of the belt strap indicate that the embalmers were not able to apply the sophisticated tying technique used during its owner’s lifetime.

Provenience

The mummy with the wooden toe was found in parts, commingled with burial relics in a looted shaft tomb cut into the rock floor of a Theban tomb chapel at Sheikh ‘Abd el-Qurna (TT95A), which had been built during the 15th century BC. Since 2016, the LHTT project has been analysing and evaluating the mixed find material from the shaft tomb and identified possible items of the female burial. The short, square-shaped shaft leading into a roughly cut, low-ceilinged chamber suggests a Third Intermediate or Late Period date of its construction (ca. 9th–6th century BC). The scarce, mixed burial remains only allow for the same wide time range.

Additional Finds

Two pieces of mummy binding, probably made of linen, were recovered from the mummy. Both display ink inscriptions: the first one shows a single hieratic docket line in the left upper corner and marks a date of year 15, but the overall composition deviates from the usual way dates were written. The second piece bears a vertical column of text with the name and filiation of the woman, a certain Tabaketnetmut, the daughter of a priest called Bakamun.

Contributors (in alphabetic order)

- Martina Aeschlimann-Langer (scientific illustrator), University of Basel

- Ahmed Amin (photographer), Egyptian Museum Cairo

- Susanne Bickel (principal investigator, Egyptologist), University of Basel

- Thomas Böni (orthopaedist), University of Zurich

- Patrick Eppenberger (MD, industrial designer), University of Zurich

- Ephraim Friedli (geodesist), ETH Zurich

- Zan Gojcic (geodesist), ETH Zurich

- Mahmoud Ibrahim (project communication Egypt), University of Basel

- Andrea Loprieno-Gnirs (field director, Egyptologist), University of Basel

- Nesrin el-Hadidi (wood conservator), University of Cairo

- Rim Hamdy (archaeobotanist), University of Cairo

- Matjaž Kačičnik (photographer), University of Basel

- Kathrin Kocher (textile conservator) Ethnographic Museum/University of Zurich

- Manal Maher (CT scan technician), Egyptian Museum Cairo

- Matthias Müller (epigrapher, Egyptologist), University of Basel

- Erico Peintner (wood conservator), University of Basel

- Klaus Powroznik (scientific photographer, archaeologist), University of Basel

- Jacques Reinhard (wickerwork expert), Laténium Neuchâtel

- Frank Rühli (second PI, MD, paleopathologist), University of Zurich

- Nadine Schönhütte (textile expert), University of Basel/TH Cologne

- Lucy Skinner (archaeologist/leather expert), British Museum London/University of Northampton

- Stephan M. Unter (computer scientist/Egyptologist), University of Basel

- André Veldmeijer (archaeologist/palaeontologist), American University in Cairo

- Caroline Vermeeren (archaeobotanist), Biax Consult, Netherlands

We are most grateful to:

- The Ministry of Antiquities

- The Egyptian Museum

- The Swiss National Research Foundation (SNF)